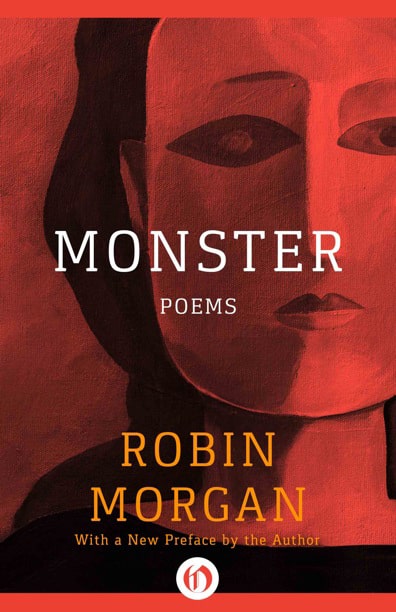

Monster

Poems

Her first book of poems sold 30,000 hardcover copies in the first six months—and was quickly termed “the anthem of the women’s movement.”

Random House (cloth) and Vintage (paperback), 1972

“‘Monster,’ the title poem, has enough energy in it to light a city block for 10 years. A terrifing, wonderful work.” —MARGE PIERCY

“Beware. This book has been banned in the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth. This slim volume looks like poetry, but it is gelignite. It will explode inside your head. Robin Morgan is a prophet with a vision of the Apocalypse. We—the women who have conspired to publish this edition, ‘pirated’ with the author’s permission, believe in Robin Morgan’s vision and—so help us—we will make it a reality.” —STATEMENT ON THE BACK COVER OF THE BRITISH EDITION

“Monster has given strength to every woman we’ve shown the poems to. And if not only reading the poems but publishing them becomes a revolutionary experience, then so much more power to sisterhood.” —MELBOURNE RADICAL FEMINISTS, AUSTRALIAN EDITION

“Since a great deal of effort has gone into trying to keep the Hughes scandals out of the limelight, it is a shame that Morgan’s poem has provoked such emotional reaction.” —DORIS LESSING

Robin Morgan’s first book of poems made its own history. Thirty thousand hardcover copies selling in the first six months alone is unheard of for any book of poems, much less for a first book by a young poet. What no one, including Morgan and her publishers, anticipated was the size and hunger of the new female readership. Poets are accustomed to audiences of twenty loyal souls, but readings drew hundreds of people; on three occasions Morgan gave readings for packed auditoriums that seated a thousand or more. The title poem, “Monster,” was quickly termed “the anthem of the Women’s Movement,” and lines from it showed up on buttons, bumper stickers, t-shirts, posters, and graffiti.

However, the book was attacked by the literary establishment because of Morgan’s poem “Arraignment,” which implied that Sylvia Plath’s suicide had been provoked by her husband Ted Hughes’ battery and womanizing. Random House, without telling Morgan, made its separate peace with Hughes, who had threatened to sue even on the basis of the revised, irony-suffused version of the poem that finally appeared in the book. The publisher agreed to withdraw all copies from any markets in the entire Commonwealth, and Hughes then agreed not to lodge suit. There was nothing Morgan could do.

But women thought otherwise. Canadian women decided to publish a “pirated” edition—”pirated” with Morgan’s permission. Within a month, women in Australia and in New Zealand published their own separate “pirated” editions. This happened all over the Commonwealth—spontaneously, furiously, astonishingly. Each edition was different, some with graphics by women, some with photos of Plath, some with both versions of “Arraignment.” Then an English women’s group published and distributed their edition—an act of special courage, since UK slander laws carry heavy sentences for printers and distributors as well as publishers.

Women all over the Commonwealth carried it further. They made it impossible for Hughes to give public poetry readings in his own country: English feminists picketed the venue with signs quoting lines from “Arraignment.” His reading tours in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States were canceled because of threatened mass protests by what came to be called “Arraignment Women,” who also repeatedly chiseled Hughes’ name off Plath’s grave marker.

A more in-depth explanation of the impact of Monster can be found in Morgan’s memoir, Saturday’s Child, and in the new preface she wrote for this digital edition.